A Traveler’s Road to Enlightenment

Hitching rides became a way of life for Jack Kerouac’s Beat Generation. Decades later, Anton Krotov is leading a movement of Russia’s globetrotting “free travelers.”

Hitching rides became a way of life for Jack Kerouac’s Beat Generation. Decades later, Anton Krotov is leading a movement of Russia’s globetrotting “free travelers.”With over 30 years of travel experience and 17 books under his belt, Anton Krotov doesn’t lack in tales from the road.

“One of my favorite stories comes from a journey on the Trans-Siberian Railroad, from Magadan back to Moscow,” said Anton Krotov, founder of the Moscow Academy of Free Travel. “My friend and I were detained by guards at a station for trying to negotiate with the train’s engineer. We went willingly, telling them about our trip, and they gave us food before handing us over to local police. We made friends with them, too, had dinner and a bath, and stayed at the chief policeman’s home before being given a special escort the next day.”

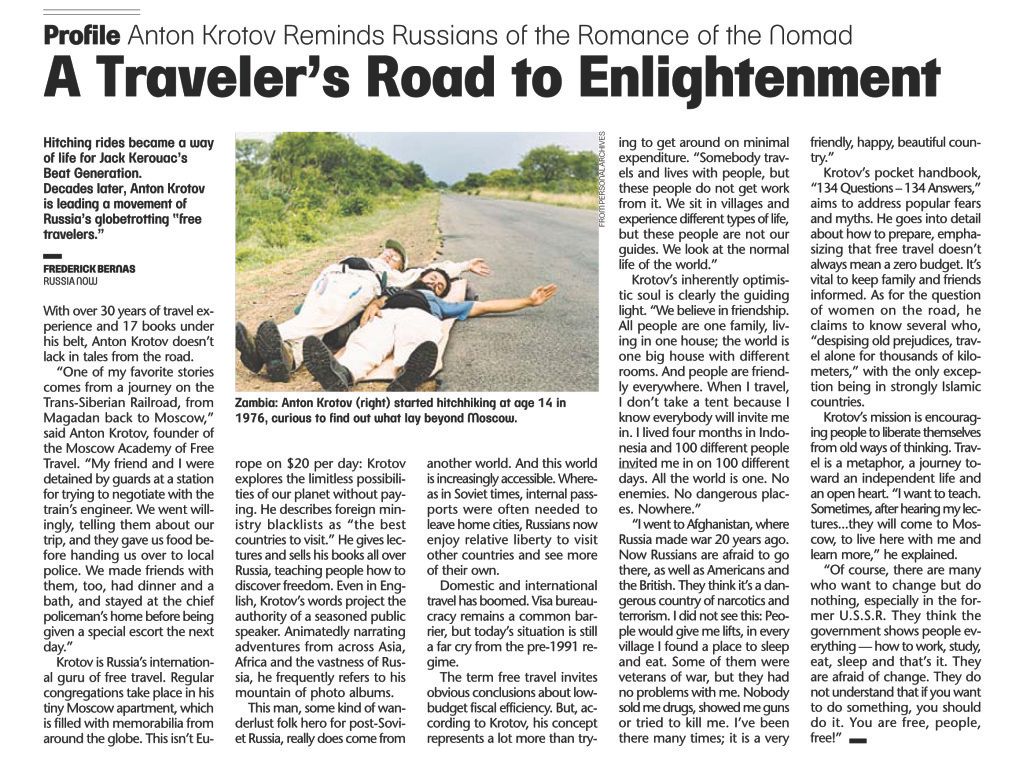

Krotov is Russia’s international guru of free travel. Regular congregations take place in his tiny Moscow apartment, which is filled with memorabilia from around the globe. This isn’t Europe on $20 per day: Krotov explores the limitless possibilities of our planet without paying. He describes foreign ministry blacklists as “the best countries to visit.” He gives lectures and sells his books all over Russia, teaching people how to discover freedom. Even in English, Krotov’s words project the authority of a seasoned public speaker. Animatedly narrating adventures from across Asia, Africa and the vastness of Russia, he frequently refers to his mountain of photo albums.

This man, some kind of wanderlust folk hero for post-Soviet Russia, really does come from another world. And this world is increasingly accessible. Whereas in Soviet times, internal passports were often needed to leave home cities, Russians now enjoy relative liberty to visit other countries and see more of their own. Domestic and international travel has boomed. Visa bureaucracy remains a common barrier, but today’s situation is still a far cry from the pre-1991 regime.

The term free travel invites obvious conclusions about low-budget fiscal efficiency. But, according to Krotov, his concept represents a lot more than trying to get around on minimal expenditure. “Somebody travels and lives with people, but these people do not get work from it. We sit in villages and experience different types of life, but these people are not our guides. We look at the normal life of the world.”

Krotov’s inherently optimistic soul is clearly the guiding light. “We believe in friendship. All people are one family, living in one house; the world is one big house with different rooms. And people are friendly everywhere. When I travel, I don’t take a tent because I know everybody will invite me in. I lived four months in Indonesia and 100 different people invited me in on 100 different days. All the world is one. No enemies. No dangerous places. Nowhere.”

“I went to Afghanistan, where Russia made war 20 years ago. Now Russians are afraid to go there, as well as Americans and the British. They think it’s a dangerous country of narcotics and terrorism. I did not see this: People would give me lifts, in every village I found a place to sleep and eat. Some of them were veterans of war, but they had no problems with me. Nobody sold me drugs, showed me guns or tried to kill me. I’ve been there many times; it is a very friendly, happy, beautiful country.”

Krotov’s pocket handbook, “134 Questions – 134 Answers,” aims to address popular fears and myths. He goes into detail about how to prepare, emphasizing that free travel doesn’t always mean a zero budget. It’s vital to keep family and friends informed. As for the question of women on the road, he claims to know several who, “despising old prejudices, travel alone for thousands of kilometers,” with the only exception being in strongly Islamic countries.

Krotov’s mission is encouraging people to liberate themselves from old ways of thinking. Travel is a metaphor, a journey toward an independent life and an open heart. “I want to teach. Sometimes, after hearing my lectures... they will come to Moscow, to live here with me and learn more,” he explained.

“Of course, there are many who want to change but do nothing, especially in the former U.S.S.R. They think the government shows people everything — how to work, study, eat, sleep and that’s it. They are afraid of change. They do not understand that if you want to do something, you should do it. You are free, people, free!

Published in Russia Now, December 2009, with The Washington Post (USA).

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home